For some time now I’ve been fascinated with the whole idea of bio-inspired computing, where we try to build algorithms that mimic the behavior of something found in nature. You may have heard of some studies and projects related to it, such as neural networks (which used to try to mimic the brain), or genetic algorithms (GA). As you probably guessed from the title, we’re going to talk about the latter.

On Genetic Algorithms

Genetic Algorithms can be classified as an optimization technique, sometimes also labeled as a subcategory of machine learning (although one can argue that most ML ideas are also optimization techniques), where we try to mimic the behavior of natural selection itself, by having an initial population that will generate new offspring (which are hopefully better than their parents) over time along with some form of mutation once in a while. The end goal is to have a population that improves over time based on some predefined metric (which we will call fitness) and achieves our objective, or adapts dynamically onto a variable fitness target. It can be also seen as a fancy way to brute force a solution 😆

A neat example of real world usage of GA is when you want to tune the hyper parameters of a neural network, or even when you want to train the network itself using GA, where you’ll use the network’s weights as your individual’s chromosomes and try a bunch of different weights until one set fits the bill. Many people have used that to beat some games, you can watch some examples here and here.

One key detail of GA is that you need to have a really good grasp about the problem you’re solving, since that’ll define your fitness function (that’s a really important keyword, keep it in mind), and the better you define it, the better your results are going to be. As an example, if you’re trying to make a GA to beat a game like Mario, you might just say that your fitness function is based on the least amount of deaths. Doing so, your “AI” might end up just outsmarting you and standing still, doing nothing and keeping the death number zeroed.

Building a Genetic Algorithm

As I said earlier, GAs try to mimic the behavior of natural selection. In order to better show how it works, I’ve chosen the 8-Queens puzzle for us to solve, mainly because it’s a problem that’s easy to visualize in my head, and also isn’t that complicated. Basically, the problem is to arrange 8 queens in a chessboard so that no queen can kill each other.

Individual representation

First of all, we need to define what an “individual” in our population is. Remember that each individual is a possible solution to our problem, in which case it’s a board where no queen can kill each other. This part is really important since you can try to “cheat” a bit in order to get your problem started in the right direction and save you some time. Thinking about our problem, one possible way to represent a possible solution would be to have an 8x8 matrix (representing the chessboard), filled with zeroes and 8 random ones (representing our queens). We’ll be using C++ from now on since we’re going to be running this on a microcontroller later.

int chessboard[8][8];

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++){

int randX = std::rand() / ((RAND_MAX + 1u) / 8);

int randY = std::rand() / ((RAND_MAX + 1u) / 8);

chessboard[randX][randY] = 1;

}

This could work, but since we already know our problem along with what the end result should be, we can take a shortcut: since we know that we can’t have 2 queens in a single row, why not only allow 1 queen per row from the beginning? Doing so means that, instead of having a big 8x8 matrix, we can go with a single array with 8 positions representing our amount of rows, where each element in that array represents where the queen is placed in that row, like so:

std::array<uint8_t, 8> rows;

for (uint8_t i = 0; i < rows.size(); i++){

uint8_t randVal = std::rand() / ((RAND_MAX + 1u) / 8);

rows[i] = randVal;

}

This saves us both space (which is really important when talking about embedded systems), along with computational time since we don’t need to worry about juggling each queen around a 8x8 matrix, nor we need to worry about collisions in each row.

Another important thing about each board is a way for us to know how well it is doing in our grand evolution scheme. For that we need to define a fitness value for it, along with a fitness function that results in that value. Our case is really simple, since all we want is a board where no queen can kill another. For that we can simply count the number of possible collisions in our board, and that’ll be our fitness function. Whenever we reach a fitness value of 0, it means that there are no collisions in our chessboard, which also means that we’ve solved the puzzle!

void checkFitness(){

fitness = 0;

// Hashtable to easily verify queens on the same column

std::array<uint8_t, 8> values;

values.fill(0);

for (uint8_t i = 0; i < rows.size(); i++){

values[rows[i]]++;

}

// Increases fitness for every queen in the same column

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < values.size(); i++){

if (values[i] > 1){

fitness += values[i] - 1;

}

}

// Increases fitness for every queen in a diagonal

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < rows.size(); i++){

if (rows[i] < 7){

auto temp = rows[i];

for (auto j = i + 1; j < rows.size(); j++){

temp += 1;

if (temp > 7)

break;

if (temp == rows[j]){

fitness++;

}

}

}

if (rows[i] > 0){

auto temp = rows[i];

for (auto j = i + 1; j < rows.size(); j++){

temp -= 1;

if (temp > 7)

break;

if (temp == rows[j]){

fitness++;

}

}

}

}

}

Wew, that came out kinda long, mainly because checking for collisions in each diagonal wasn’t that easy and I’m also bad at code, but we do what we can.

Avoid getting stuck

If you think about our problem as a mathematical function, we’ll have a specific (or multiple) place where our target results lies in (global maxima or minima, depending on your problem), and others that are really close to our target, but not quite there yet (local maxima and minimas).

Since we’re trying to optimize a function in a pseudo-random way that depends on the combination of individuals over time, it’s easy to get our entire population to compromise of the same individuals that are quite close to our objective, but still no there yet, with no way to improve since any combination of 2 equal individuals would generate an individual that’s just like their parents. That’s why keeping our gene pool diverse is so important during the whole process (that makes you wonder, huh?).

|

|---|

| What happens when you get stuck in a local minimum |

Mutation

Along with keeping our gene pool diverse, how else can we avoid a local minimum? That’s where mutation comes in, a key part of GAs which occurs once in a while and modifies an individual in a random way in order to allow us to explore better our problem space and helps us to get out of a local minimum if we ever get stuck. In our case, we can simply move a queen in a random row into another random position, like so:

void mutate(){

uint8_t temp1 = (std::rand() / ((RAND_MAX + 1u) / 8));

uint8_t temp2 = (std::rand() / ((RAND_MAX + 1u) / 8));

rows[temp1] = temp2;

}

Crossover

Another key element of GAs is the crossover step, also called recombination, where we take 2 individuals to generate a new one with some really chic algorithm that will guarantee that they’re the best parents and will create a really nice offspring, or just randomly like 2 drunk people in Vegas (spoiler: we’re going to stick with this one).

Since each board in our population is a single array with 8 elements, we can generate a new board by simply picking 2 random individuals, selecting a random number X between 1 and 7, picking the first X elements of the fist parent and combining those with the last 8-X elements of our second individual to generate our new baby, always with a chance to mutate it randomly.

crossover(std::array<uint8_t, 8> const &parent1, std::array<uint8_t, 8> const &parent2,

uint8_t crossoverPoint, uint16_t mutationRatio){

// Merges the beggining of the first parent with the remaning of our

// second parent into our new individual

for (uint8_t i = 0; i < crossoverPoint; i++){

rows[i] = parent1[i];

}

for (uint8_t i = crossoverPoint; i < rows.size(); i++){

rows[i] = parent2[i];

}

if (1 == (std::rand() / ((RAND_MAX + 1u) / mutationRatio))){

mutate();

}

checkFitness();

}

By now we should have everything we need in order to define what our individual is, and the operations we can perform on it, resulting in this simple class:

class board{

public:

board();

board(

std::array<uint8_t, 8> const &parent1, std::array<uint8_t, 8> const &parent2,

uint8_t crossoverPoint, uint16_t mutationRatio = 10);

~board();

std::array<uint8_t, 8> rows;

uint8_t fitness;

void checkFitness();

void mutate();

};

You may notice that I’ve changed our crossover function to be an overload of our board constructor, that’ll make more sense once we start talking about population. Another thing is that the mutation rate default value is 10, which means that there’s a 10% chance of a mutation to occur. It’s kinda high, however it worked well enough for me, although your mileage may vary.

Initializing our first population

Know that we know how to represent a single individual, along with its fitness value, we need our starting pool of individuals. One thing to keep in mind is the number of individuals that we’ll keep during each generation of our population. Make this number too low, and you’ll need a lot of time to reach your solution. Make it large enough and you’ll run out of RAM faster than opening lots of tabs in Chrome.

|

|---|

| What happens when you run out of RAM on an embedded device |

Just to give you some food for thought, if we had an infinite amount of RAM, we could try to initialize an infinite number of random arrangements, and I bet that one of those random individuals would actually be a perfect solution. The 8 queens puzzle has 4,426,165,368 possible arrangements, with only 92 possible solutions, which means that there’s a solution for approximately every 48,110,493 arrangements we’d find a solution. Doing some quick maths, each board that we coded requires 8 bytes of space, which means that with ~385MB of memory we could find a solution by simply initializing random boards, and with ~35GB of RAM we could probably find all of the solutions in the same way. Too bad we will be working with a chip that only has a few KB of RAM.

Back to our population, we’ll keep it simple and make our population be just a list of boards:

population(uint32_t size){

this->size = size;

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < size; i++){

board temp;

boards.push_back(temp);

}

sortPopulation();

}

See that sort there, in the last line? It’ll make our lives easier later on, but all it does is just sort our vector based on the fitness value of each board.

sortPopulation(){

std::sort(

boards.begin(), boards.end(), [](board a, board b) {

return a.fitness < b.fitness;

});

}

Reproducing

Now we get to increase our population my mating some couples to generate our desired number of new offspring to add to our pretty civilization. Keep in mind that there are many ways to select your couples, like picking the best ones from your population (also called an elitist selection), or giving them a chance proportional to their fitness (also called roulette wheel selection). Also notice that usually what people do is:

- Generate 2 new individuals

- Replace their parents with the new generated individuals

This makes it easier to control the size of your population as well as making each generation actually look like a real life generation, where children end up replacing their parents in the world. Well, I wanted to try something different, so I’ll be generating just a single new individual from every crossover, and I’ll be making use of an extra step to trim our population after that.

I’ve chosen to pick both parents randomly because I like to believe that there’s nothing more fair than something random.

reproduce(uint32_t amount){

auto populationSize = boards.size();

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < amount; i++){

auto first = (std::rand() / ((RAND_MAX + 1u) / populationSize));

auto second = (std::rand() / ((RAND_MAX + 1u) / populationSize));

uint8_t crossoverPoint = 1 + (std::rand() / ((RAND_MAX + 1u) / 7));

board temp((boards[first].rows), (boards[second].rows), crossoverPoint);

boards.push_back(temp);

}

sortPopulation();

}

See how that overload for a new board came in handy? I can generate a new one by simply passing it’s parents and how much of each parent it should get.

Trimming our population

We now have all of our previous population living along together with their new offspring, which is really nice and cute. However, just like nature, we need to get rid of some of those, or else we’ll run out of RAM eventually. We could simply chop off the worst-performing individuals in our population, but do you remember what I said about keeping diversity before? In order to not get stuck in a local minimum, I’ll be keeping the worst 10% of our current population, and then getting rid of the other ones until we get back to our original population size.

purge(){

uint32_t len = boards.size();

// Let's keep diversity in our gene pool

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < size / 10; i++){

std::iter_swap(boards.begin() + size - i, boards.end() - i);

}

for (uint32_t i = size; i < len; i++){

boards.pop_back();

}

}

I had previously awfully named this step as selection, when that should be the process where we select the parents for our new offspring, but after a quick review from a friend of mine, it’s now properly called purge.

Anyway, putting this all together gives us a really clean population:

class population{

public:

population();

population(uint32_t size);

~population();

std::vector<board> boards;

uint8_t size;

void sortPopulation();

void reproduce(uint32_t amount = 50);

void purge();

};

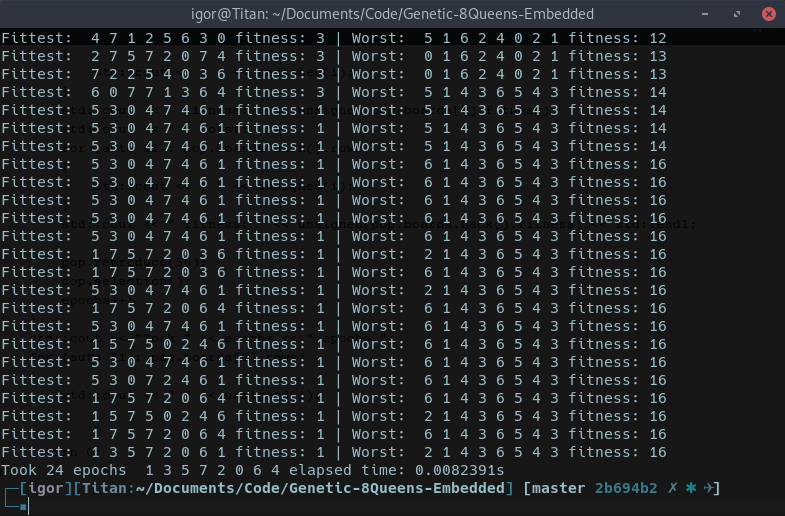

Trying it out

Since we finally have all the building blocks needed for our genetic algorithm, let’s try it out in our computers and see how it does before attempting to put it into a microcontroller:

int main(int argc, char const *argv[]){

std::srand(std::time(nullptr));

population pop(100);

int epochs = 0;

while (pop.boards[0].fitness != 0)

{

std::cout << "Fittest: ";

for (auto &i : pop.boards[0].rows)

{

std::cout << " " << unsigned(i);

}

std::cout << " fitness: " << unsigned(pop.boards[0].fitness);

std::cout << " | Worst: ";

for (auto &i : pop.boards.back().rows)

{

std::cout << " " << unsigned(i);

}

std::cout << " fitness: " << unsigned(pop.boards.back().fitness) << std::endl;

pop.reproduce(50);

pop.purge();

epochs++;

}

std::cout << "Took " << epochs << " epochs ";

for (auto &i : pop.boards[0].rows)

{

std::cout << " " << unsigned(i);

}

return 0;

}

|

|---|

| Gotta go fast |

Hey, look at that, it works! We could wrap it up for now, but I also wrote “embedded” on the title, so we will need to work on that.

Going bare-metal

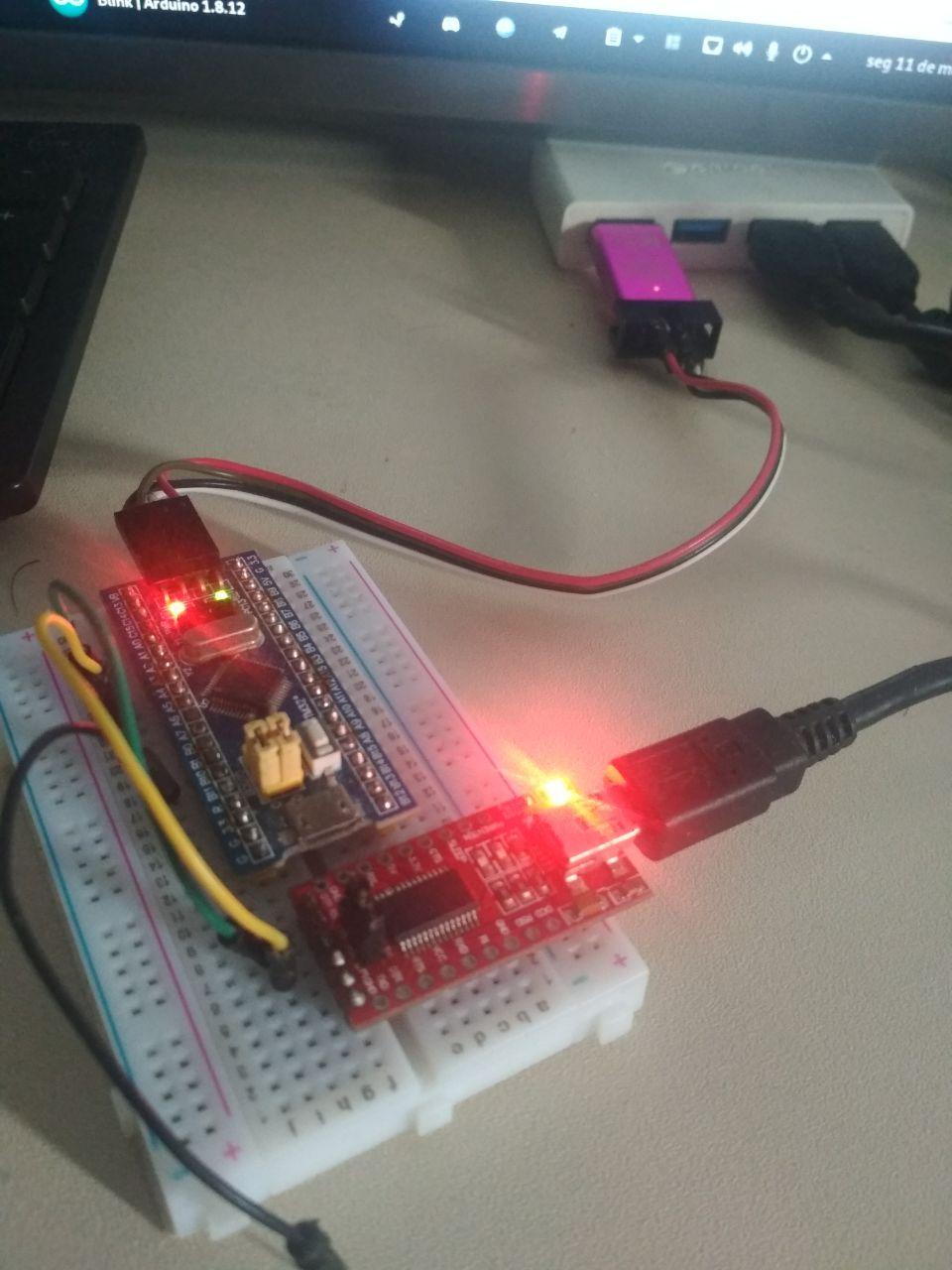

I guess an Arduino would suffice for that, and also is easily accessible by most people. However, all I had in hands was a Blue Pill, a nice little dev board that contains an ARM based microcontroller running at blazing 72MHz, with 64KiB of flash storage and 20KiB of RAM. That may not sound like a lot if you compare to your computer, but is a lot more than your usual Arduino and should be actually overkill for what we’re trying to do here.

|

|---|

| Blue pill with a ST-Link clone (pink) and an USB-Serial converter (red) |

To make things easier, I’ll be making use of Mbed, which will provide us enough abstractions and make stuff pretty Arduino-like.

Remember that code we used for our desktop? With some minimal changes we’ll be able to run that in our little board.

#include "mbed.h"

#include "genetic.cpp"

Serial pc(PA_2, PA_3); // TX, RX

AnalogIn noise(PB_1);

Timer t;

int main()

{

uint16_t val = noise.read_u16();

std::srand(val);

t.start();

population pop(150);

int epochs = 0;

while (pop.boards[0].fitness != 0)

{

pc.printf("Fittest: ");

for (auto &i : pop.boards[0].rows)

{

pc.printf(" %u", i);

}

pc.printf(" fitness: %u", pop.boards[0].fitness);

pc.printf(" | Worst: ");

for (auto &i : pop.boards.back().rows)

{

pc.printf(" %u", i);

}

pc.printf(" fitness: %u\r\n", pop.boards.back().fitness);

pop.reproduce(100);

pop.purge();

epochs++;

}

pc.printf("Took %d epochs ", epochs);

for (auto &i : pop.boards[0].rows)

{

pc.printf(" %u", i);

}

t.stop();

pc.printf(" time: %fs", t.read());

}

The major change that we had to do was to get rid of all cout calls, and instead use a printf into our serial port that’s connected to an USB-Serial converter to my PC. Another thing was that, since we have no system to provide us a source of entropy for our pseudo-random number generator, I simply left a jumper attached to a pin floating in the air to read some noise and use that as a seed for our RNG.

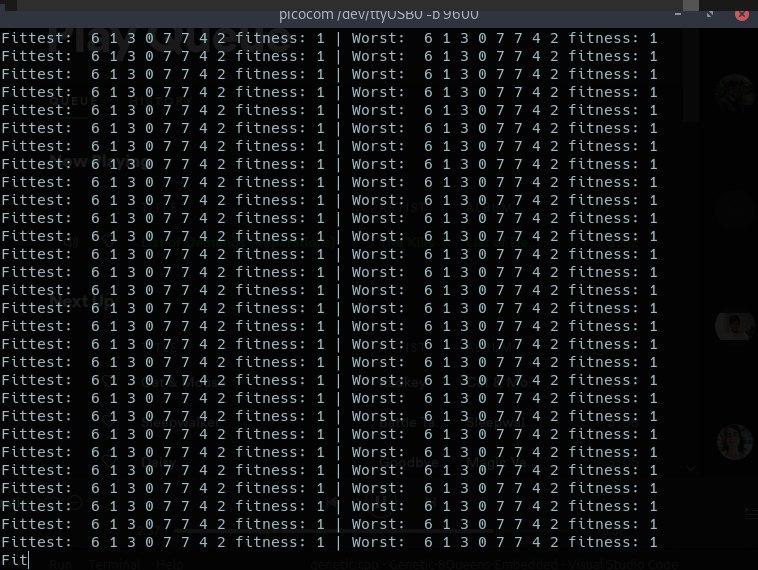

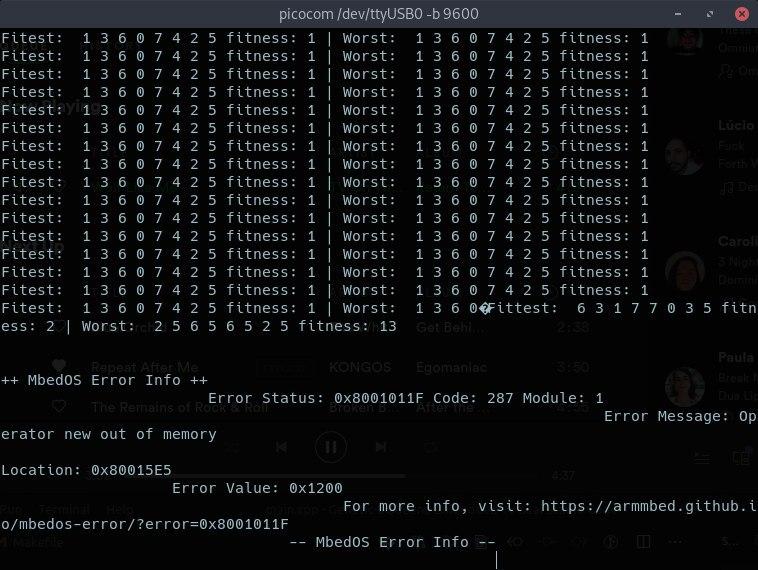

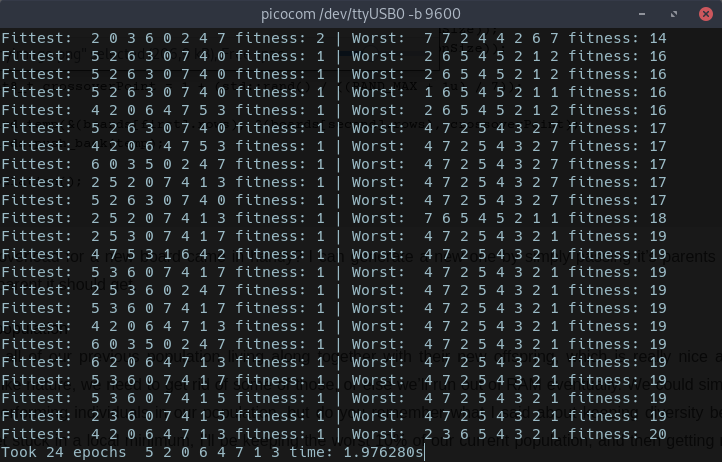

After compiling and flashing everything, let’s see how it works out:

|

|---|

| Not so shabby |

Wew, it works! And it isn’t even that slow when compared to a regular PC if you remember that it’s a 72MHz chip against a multi GHz machine.

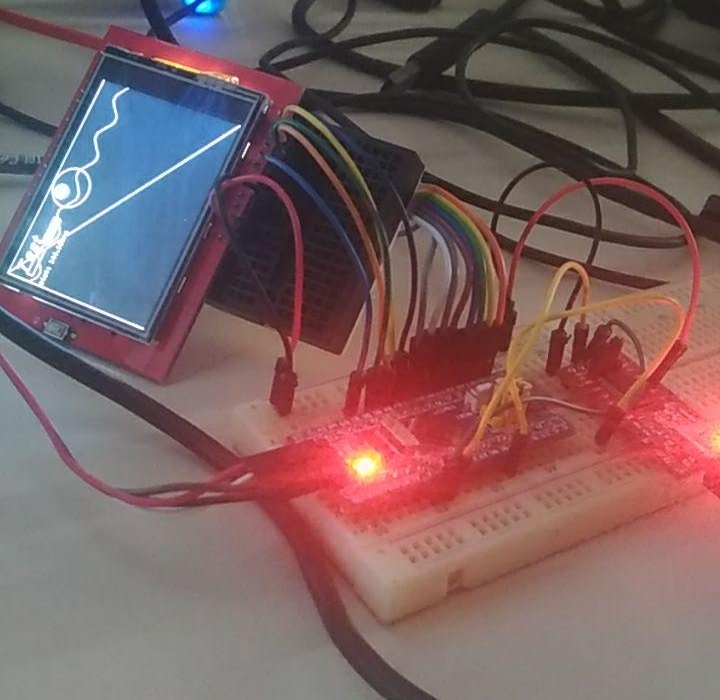

But there’s something missing… Maybe if we add some blinking stuff, like a LED! Better yet, let’s add a screen to our board!

|

|---|

| Lots of wires in there |

Thanks to the UniGraphic lib, using that screen was a breeze. I won’t bother you with the details of the code to draw everything, but you can have a look at it here. Let’s spin it up and see how it goes:

Really pretty, ain’t it? In case you want to try it out, feel free to grab the code on my github, and don’t hesitate to ask any questions or chat with me :)